RSS at 100: Struggle for Relevance in the Modi era

- Nabeel Bhattacharya

- Aug 23, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Sep 14, 2025

As the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh celebrates its centenary, the organisation finds itself both triumphant and unsettled. Its swayamsevaks dominate India’s political landscape in a way Balasaheb Deoras or M.S. Golwalkar could only dream of. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, himself a lifelong pracharak, has delivered the RSS its most dazzling political success in history. And yet, in Nagpur, there is restlessness, even resentment. The Sangh, once the unquestioned elder brother of the BJP, now finds itself scolding from the sidelines, while its political child has become too large, too confident, and too independent to be lectured.

This tension has burst into public view repeatedly since June 2024, although keen observers could see it building, especially after the 2019 bumper victory. On the heels of an election where the BJP lost its majority and was forced to rely on allies, Mohan Bhagwat, the RSS Sarsanghchalak, struck a tone more of rebuke than celebration. “A true sevak is never arrogant,” he intoned. “In the elections, decorum was not maintained.” It was the kind of sermon that once made Vajpayee bristle.

At Pune, in December 2024, Bhagwat turned his gaze on Ayodhya. He reminded his audience that the Ram Mandir was a matter of faith, not a political toy, and condemned attempts to stoke new temple disputes out of hatred. By July 2025, he went further still: “When you turn 75, you should stop now and make way for others.” No name was mentioned, but everyone knew who he meant. The opposition gleefully seized upon it as a veiled strike at Narendra Modi. The RSS denied it, the BJP dismissed the row as needless, but the message hung in the air.

Since publishing this, a new development has happened. PM Modi has extended another olive branch to Mohan Bhagwat on his 75th birthday on 11th September, publishing effusive tributes across newspapers. The gesture carries multiple meanings: a symbolic reminder that Bhagwat himself is now 75, and another attempt to mend ties with the RSS chief. It came soon after Bhagwat had publicly clarified that turning 75 was not a leadership cut-off - a statement with clear political undertones.

For veterans of the Vajpayee years, this was déjà vu.

KS Sudarshan had made a habit of chastising the BJP’s top brass. Vajpayee’s entire tenure as Prime Minister witnessed constant bickering from Nagpur. After the BJP’s shock 2004 defeat, the RSS even demanded that Vajpayee and Advani step aside for the next generation. Vajpayee, famously prickly about autonomy, was livid. But he was tired, then ill, and soon retired into silence.

Vajapyee vs RSS was not new. In 1991, RSS backed Murli Manohar Joshi as BJP President (1991–1993) and projected him through the ill-fated Ekta Yatra (that ironically had narendra Modi as the main organiser). This was widely seen as an attempt to elevate another Brahmin leader from the Hindi heartland and semi-challenge Vajpayee’s preeminence.

Vajpayee himself had skipped contesting the 1989 Lok Sabha elections — the only time in his career — and was absent from the 1988 Palampur conference when the BJP officially adopted the Ram Mandir resolution. Against this backdrop, Joshi was being positioned by the RSS as a possible replacement for Vajpayee, an alternative Brahmin leader who could be the Sangh’s ideological anchor.

When factional fights paralysed the BJP and Advani struggled to enthuse cadres, the RSS repeatedly stepped in. Advani was offered one last chance in 2009 to prove himself, but the Jinnah episode of 2005 had already sealed his decline. He was first replaced by Rajnath Singh as BJP president, and after the 2009 defeat by Gadkari, parachuted in from Nagpur. Yet both experiments faltered, leaving the organisation adrift until Modi’s rise post-2012 restored unity and direction.

The RSS-BJP relationship has always followed this pattern: parental when it can be, advisory when it must be, and resentful when ignored. The difference now is that Modi’s BJP no longer needs Nagpur’s logistical muscle.

Vajpayee still leaned on shakha cadre for rallies and campaigns. Modi and Amit Shah have built a formidable machine that has penetrated regions where the Sangh had failed for decades - Bengal, Assam, Tripura, even Kerala. The RSS can sermonise, but it can no longer claim indispensability. And yet, the interventions of 2024 and 2025 cut deeper, because they expose the Sangh’s real anxiety: Modi has cut it down to size, and the Sangh does not know how to respond.

If this dynamic needed a symbol, it came in the unlikely form of Sanjay Joshi. Once, Joshi was the most powerful organiser in Gujarat BJP, a mild-looking pracharak with immense authority. In the 1990s, while Modi was sidelined to organisational posts in Himachal and Haryana, Joshi ruled Gujarat BJP with Nagpur’s blessing. But when Modi returned as Chief Minister in 2001, Joshi became the only man who could challenge him from within. Four years later, at the BJP national executive in 2005, a sex CD allegedly involving Joshi was leaked and circulated. The scandal destroyed him overnight. Everyone knew where the knives had come from. Joshi resigned in disgrace, and Modi was rid of his greatest internal rival. Yet Joshi never disappeared entirely. He lingered in the margins, occasionally resurfacing, drawing loyalty from cadres who had not forgotten him.

Today, whispers in Delhi suggest Joshi is being considered for BJP National President or even General Secretary (Organisation). For Modi, who buried Joshi two decades ago, the thought of his resurrection now - when Modi is at his peak but dented by a reduced majority - is a humiliation. For the RSS, floating Joshi’s name is not about rehabilitating an old warhorse. It is a calculated insult, a reminder to Modi that Nagpur will not allow him to monopolise the BJP as he has tried to do since 2019. The delay in naming a new BJP president only adds to the sense of tug-of-war. Modi and Shah want a loyalist; Nagpur wants one of its own. In between hovers Joshi’s ghost, a man finished by Modi, now dangled like a sword over his head.

This is politics, Sangh-style. At the grassroots, swayamsevaks still toil in obscurity. In the forests of Chhattisgarh, Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram schools, first built on land donated by Dilip Singh Judev’s family, continue their work. Ekal Vidyalayas spread literacy in tribal villages. Thousands of ordinary pracharaks, nameless to the outside world, run health camps and relief work, especially during disasters. But at the top, the RSS now lives in a five-star bubble. Leaders shuttle between Delhi and Nagpur, dabbling in palace intrigue, whispering about appointments, claiming credit for victories, blaming the BJP for defeats.

The Vice-President saga of 2025 exemplified this tug-of-war. Jagdeep Dhankhar, once seen as Modi’s man, was abruptly forced to resign. In his place came CP Radhakrishnan, a dyed-in-the-wool RSS loyalist. Modi sacrificed an ally to mollify Nagpur, but he also showed that the timing and terms of such sacrifices would be dictated by him, not them. It unnerved leaders across both BJP and RSS, who read it as a signal: Modi may be weaker post-2024, but he remains firmly in control.

The rise of Narendra Modi took place when the RSS and BJP were struggling for direction. After Advani’s controversial Jinnah remark in 2005, the RSS forced him to resign as party president. Rajnath Singh was appointed in his place to stabilise the organisation and restore order.

However, infighting persisted within the BJP leadership in Delhi. The coterie of leaders - Sushma Swaraj, Pramod Mahajan (tragically killed by his brother a year later), Arun Jaitley, Ananth Kumar, and others — kept jockeying for influence, leaving the party divided and rudderless. The BJP continued losing elections even as Manmohan Singh’s popularity as a clean and steady technocrat grew. By 2008–2009, the political climate should have been an ideal pitch for the BJP: India had witnessed repeated terrorist attacks, including the 2008 Mumbai carnage, while the Congress sought to discredit the Sangh Parivar through the “Hindu saffron terror” narrative and dubious conspiracy cases. Yet Advani failed to deliver. The economy too, provided a counterweight: India was riding the global boom of 2004–2008, powered by Vajpayee-era reforms and infrastructure expansion (1998–2004). As a largely consumption-driven rather than export-led economy, India was relatively insulated from the 2008 global financial crisis. In this context, the BJP’s campaign failed to resonate, and Advani’s leadership appeared exhausted.

After the 2009 defeat, the RSS parachuted in Nitin Gadkari as party president — their “blue-eyed boy” chosen to usher in generational change and curtail the Delhi old guard. But Gadkari too faltered when the Purti files controversy erupted, leaving the party rudderless once again.

Meanwhile, the national mood was shaped by what I call the “ABC effect”:

Anna Hazare’s anti-corruption agitation, Baba Ramdev’s mass mobilisations, and CIA-linked activism channelled through Rockefeller Foundation networks that helped incubate the Aam Aadmi Party. These protests mirrored Arab Spring–style colour revolutions — with the same format being successfully implemented in the subcontinent in the last three years, as seen in Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka.

Yet the corruption scandals that fuelled these movements - 2G, the Coal Scam, the supposed ₹1.76 lakh crore telecom loss - would eventually collapse in court, with every accused acquitted. In hindsight, these episodes exposed how manufactured narratives, seeded from outside but anchored in genuine public grievances, can destabilise institutions — the same playbook that continues to be seen even today.

The RSS itself was confused in this period under Mohan Bhagwat’s leadership, who had just become Sarsanghchalak in 2009. It was pushed into a contradictory experiment that made little sense for a Hindu cultural organisation — something perhaps more natural for the BJP to attempt, but not for the RSS itself. Most notably, this took shape in the launch of the Muslim Rashtriya Manch (MRM) in 2012, an outreach platform meant to bring Muslims under the Sangh’s umbrella by promoting dialogue on cultural nationalism, cow protection, and opposition to terrorism.

But its very creation raised questions: why did a self-consciously Hindu organisation feel the need to carve out a separate Muslim front, rather than integrate minorities into its existing structures? The move looked less like conviction and more like tactical hedging.

In many ways, this was Bhagwat’s own version of the “monkey-balancing” that had undone Advani in 2005, when his Jinnah comments tried to please one audience while alienating another. Bhagwat, too, seemed uncertain - trying to placate critics of the Sangh by showing a “softer face,” but only confusing the cadre. By 2017–18, Bhagwat himself privately admitted at a local shakha - when asked point-blank by a friend of mine who used to go there regularly - that launching the Muslim Rashtriya Manch had been a mistake.

The true turning point came only after Modi’s third consecutive Gujarat victory in December 2012. His emphatic mandate electrified BJP cadres, forcing the RSS to finally endorse him. By September 2013, Modi was formally declared the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate. A sulking Advani briefly resigned in protest but returned the next day to fall in line. From that point, Modi revived the demoralised BJP–RSS combine and delivered the historic 2014 mandate.

This is why Bhagwat’s rebukes matter less for their content than for what they reveal. There is no ideological rupture here.

Modi remains the Sangh’s most faithful son in worldview.

His nationalism, civilisational vocabulary, rejection of westernisation, and embrace of Hindu assertiveness are all pure RSS. But his style is another matter. Modi has broadened Hindutva to embrace Sikhs, Tamils, tribals, and diverse strands of Hindu identity. The RSS, by contrast, remains trapped in a rigid template: Hindi, North Indian cultural symbols, one-size-fits-all Hinduism. It is telling that Bengal and Kerala host some of the Sangh’s largest shakhas, yet electorally the BJP struggled there until the Modi era. Under Modi, BJP became West Bengal’s main opposition party and won its first Lok Sabha seat in Kerala in 2024. The RSS never adapted to animistic tribal traditions or Tamil cultural idioms. Modi, by contrast, speaks the language of a modern, expansive Hindutva that can draw in constituencies the Sangh never reached.

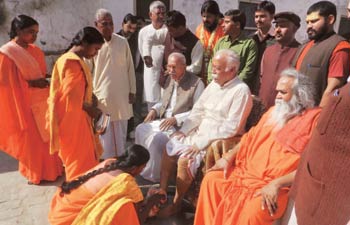

Modi washing feet vs Mohan Bhagwat getting his feet washed

This divergence was visible even before Modi became Prime Minister. In 2000, Karan Thapar, interviewing KS Sudarshan, encountered Modi.

Modi told him bluntly: “Mediocrity has crept into the RSS. It no longer stands for excellence.”

Thapar later confessed he was stunned - these were words he expected from leftist critics, not a man who had grown inside the organisation. But Modi was diagnosing what many already knew: despite its vast cadre network, the RSS had failed to build mainstream institutions of social service. Christian missions had schools and colleges. Leftist fronts had newspapers and unions. Spiritual sects like Sai Baba’s, Radha Soami, or Swadhyaya had built vast empires. The RSS had little to show. It had not produced a single university of note, not a newspaper of national reach, not even a think tank of serious influence. The Vivekananda International Foundation, the BJP-RSS ecosystem’s most significant think tank, was created by Ajit Doval, not the Sangh.

The RSS survived on palace politics, inserting itself into BJP affairs, but never built enduring social institutions.

There are, of course, exceptions – flashes of individual brilliance. The Judevs and their tribal service. Kelkar and ABVP’s rise in campuses. The steady growth of Ekal Vidyalayas. The VHP under Ashok Singhal’s leadership, which transformed the Ram Janmabhoomi movement into a mass political force. But they are exceptions. The institution itself has been marked by mediocrity, and Modi’s critique remains true a quarter-century later. At the grassroots, there is toil. At the top, there is indulgence.

RSS's success is built on individual brilliance

This is why the Sangh’s statements since June 2024 feel both familiar and hollow. The RSS has always rebuked its political child when it grows too independent. It did it with Vajpayee. It is doing it with Modi. But Vajpayee needed the RSS; Modi does not. JP Nadda said it openly before the 2024 elections: "the BJP no longer needs RSS to run its affairs". That is the real wound. The RSS can float Sanjay Joshi’s name, it can sermonise about arrogance and humility, but it cannot command obedience. Modi has made it clear: ideological alignment will remain, palace politics will not.

On the other hand, Modi - though he has decisively clipped the RSS’s role in the BJP’s organisational core - has also extended gestures of reconciliation to Nagpur, seeking to ease the post-2024 tug-of-war. Crucially, these overtures came only after the BJP’s victories in Haryana and Maharashtra restored his political mojo, allowing him to reach out from a position of strength rather than vulnerability. In March 2025, he visited the RSS headquarters in Nagpur - his first since he became PM, and only the second such visit by a sitting Prime Minister, the last being Vajpayee. The optics were deliberate: Modi chose the Sangh’s centenary year to step back into Hedgewar Bhavan, signalling respect even as he holds the reins firmly in Delhi. A few months later, in his Independence Day speech from the Red Fort, he mentioned the RSS for the very first time as Prime Minister. It could be read simply as a centenary courtesy, yet the timing mattered. He could have done so the year before, but waited until after the 2024 election setback and Bhagwat’s pointed barbs.

Taken together, the visit and the speech were less about deference and more about reconciliation — Modi’s way of acknowledging the Sangh’s symbolic authority while quietly asserting that the terms of the relationship will be set by him.

The BJP–RSS relationship, for all its internal tussles, has been marked by a discipline rare in Indian politics - the friction seldom spills into the open beyond the occasional offhanded remark, a sharp contrast to the Congress where leaks and insider briefings surface within minutes of closed-door meetings; this restraint reflects a shared dedication to the larger political cause, a discipline that has ensured they do not wound themselves publicly as they often did in the Vajpayee era.

And so, as the RSS marks its hundredth year, it faces an existential choice. It can continue dabbling in palace intrigue, inserting itself into BJP appointments, claiming credit in victories and blaming defeats on arrogance, living in five-star comfort while swayamsevaks sweat in the field. Or it can transform itself into what Modi implied back in 2000: a civilisational service organisation, with schools, think tanks, cultural institutions, and a reach that matches its political child. If it does not, it risks irrelevance in the very moment of its greatest triumph.

The Vajpayee era ended with Sudarshan scolding a Prime Minister who still needed him. The Modi era now has Bhagwat scolding a Prime Minister who does not. That is the essential difference. The BJP has outgrown its parent. The Sangh can remain the elder brother in palace politics, or it can reimagine itself as the elder statesman of civilisational service. At one hundred, the choice is starker than ever.

Sources:

Mohan Bhagwat: True sevak is never arrogant… in polls, decorum was not maintained, Indian Express (June 2024)

Mohan Bhagwat: Ram temple matter of faith, raking up new issues unacceptable, Indian Express (December 2024)

Mohan Bhagwat suggests leaders should ‘step aside’ after 75, Oppn calls remark a ‘reminder to Modi’, ThePrint (July 2025)

“Go, Mr. Modi, and go now", Sunday Sentiments, ITV (March 2002)

“Sex and the CD: Sanjay Joshi's rise and fall”, Rediff (December 2005)

“BJP in a soup; Sanjay Joshi quits after sex scandal”, Times of India (December 2005)

“RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat bats for inclusive society; frowns upon new disputes", New Indian Express (December 2024)

“RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat draws the line at 75. India’s politics stares at the Modi Exception”, ThePrint (July 2025)

“Nadda on BJP-RSS ties: We have grown, more capable now… the BJP runs itself”

The Indian Express (May, 2024)

“RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat says leaders should retire at 75, Congress asks PM Modi to pick up the bag”, Economic Times (July 2025)

"Never Said Someone Should Retire: RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat On 75-Year Age Limit", NDTV (Aug 2025)

Comments